In the long and labyrinthine history of Anytown, there’s no figure more mysterious or beloved than the Man with the Gold Car. The ageless blond Adonis, with his perfectly quaffed, neatly trimmed and parted fade, ice-blue eyes like twin glacier lakes, and serene understated smile, has been a fixture in photographs of and at parties given by the city’s richest, most glamorous, and most powerful since his first appearance here more than 100 years ago, standing as he did at the side of the legendary Senator Bertram G. Tidwell Sr. Right away the nameless, nearly mute “golden god” as the subject of intense speculation, gossip, and adoration—the aforementioned “golden god” appellation was a popular early descriptor for the Man among Anytown and Cap City journos—but he was also the linchpin of many conspiracy theories and ugly rumors at a time when the atmosphere was sufficiently oxygen-rich to allow such unpleasantness to live, thrive, and proliferate. Nonetheless, he persisted.

Until now, it seems.

Earlier this week, an as-yet-unnamed individual is said to have met with newly-elected Anytown District Attorney Dixon Condon regarding an accusation against the Man with the Gold Car that Condon has described succinctly but powerfully… ominously as “truly appalling.” A source within the DA’s office further elaborated under condition of anonymity that the alleged conduct is “sexual in nature” and “yucky, real yucky.”

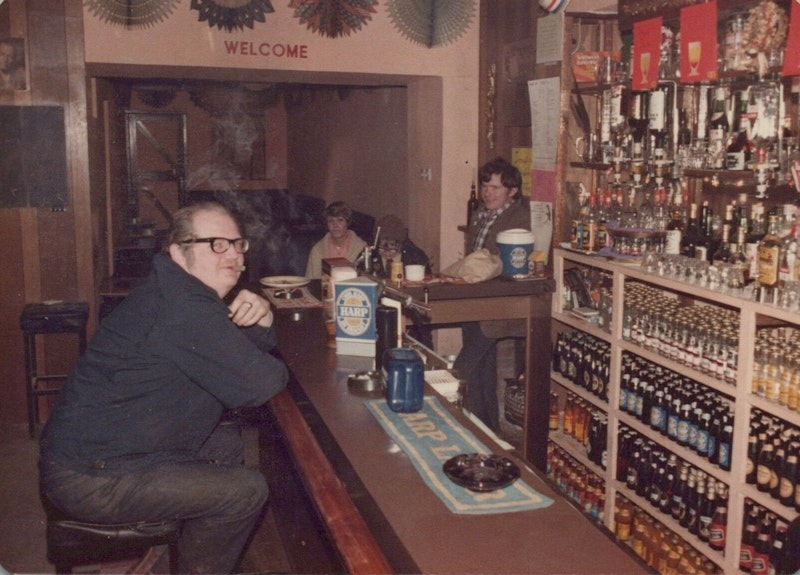

“Alright, knock it off. Knock it off!” Servais croaked, taking a final drag of his unfiltered Lucky before stubbing it out aggressively in the heavy brass ashtray on the bar before him.

Brian Powell continued reading silently for several more seconds before dropping the folded newspaper and taking a drink of his neat Old Overholt. “What do you think?” he asked.

Servais looked sideways at him through narrowed eyes. “It’s bunko, kid—total horse pucky. You kiddin’ me?”

As no elaboration or clarification followed at any point during the several minutes of near-silence that followed, Powell finally hazarded the meekly-voiced question on his mind: “Why?”

Servais lit another Lucky, took a couple of unhurried drags, sighed, then said at last in his distinctive, oddly constricted rasp, “Terry Steinbach. Remember him?”

Powell nodded. “Oh, sure. Yeah. Great catcher for some good A’s ball clubs.”

Servais’ hazel eyes widened slightly along with the sudden and barely perceptible flaring of his nostrils. “Bah! Wet noodle for an arm and after Big Mac stuck a needle in his ass and introduced him to the longball he thought it was his solemn, sworn duty to club taters all the goddamn time.”

“He did hit, what, 30 one year? Not b—”

Servais slammed the coarse palm of his leathery, scab-knuckled hand on the bartop, drawing a few startled glances from the wretched refuse hiding in the dreary, darkened pub’s broken-down booths from the harsh early afternoon light of the outside world. “To hell with the dingers! I don’t give a flyin’ fuck about the dingers! I’m talking about catching pitchers, calling a good game! That’s what it’s about. And Steinie, he knew how to call a game—more or less—which is why they kept him in pads as long as they did. Nothin’ to do with the fuckin’ moon shots you stupid assholes get so hard in the fuckin’ pants for. Christ...” He took a pull from his smoke and exhaled sharply through his nostrils, a vein pulsing at the corner of his forehead. “The guys who matter trusted him to make the calls that needed made. Understand?”

“So, uh, which one is the Man? Is he Steinbach or La Russa? Or, uh, Art Howe? Or what?”

Servais poured each of them a drink from the bottle of Old Overholt. He picked up his own glass, swirled the deep amber liquid round and round, studied the contents of the glass, glanced two or three times at Powell. He threw back the drink, swallowed and savored the pleasing burn and bite of the rye. Fixing his stare on Powell, he said at last, “Well, he ain’t Todd Van Poppel,” and grinned a grizzly grin.

“Nailed to the floor”—that was how the body was described in most of the reports, both written in the papers, on news sites, blogs, and social media, and spoken on the evening news on TV and radio, but it would be more accurate to say “staked” rather than “nailed,” for instead of nails of any description there were foot-long rebar tent stakes driven through the flesh and in a few instances bones of the corpse and into the white carpet (now stained liberally with blood that’d turned wine-dark as it soaked into the shag and dried), and beneath that the wooden floor. In spite of this and other seemingly problematic details—the extreme state of disfigurement that the dead man’s face was in at the time of his body’s discovery, reports of screams and cries for help from the deceased’s home by neighbors and passersby who called 911, the absence of any tool or implement with which the individual would’ve used to stake himself to the floor—Oliver Dabb’s death was ruled a suicide, and the note, written in blood and a variety of condiments and other, as-yet-unidentified, substances on the off-white walls of the living room and hallway was thought to be the young Anytown Gazzetteer reporter’s farewell to the world.

The message read: “I’m a Ten-Cent Daddy, I’m a Big Fuck Baby, and yes, I am that PISS LOVIN’ MAN.”