Carl Becker writes in his “Everyman His Own Historian” address that “the history that does work in the world… is living history, that pattern of remembered events, whether true or false, that enlarges and enriches the specious present, the specious present of Mr. Everyman.” This is intended to serve as a valuable reminder that history ought to be remade to suit the needs of whatever generation writes it, in order that we members of that generation might “make use” of history so as “to correct and rationalize for common use Mr. Everyman’s mythological adaptation of what actually happened.”

When I first read this address two decades ago, I considered it more small “d” democratic than it actually is. The address, far from being a plea for “Mr. Everyman” to sit down and write his own history, is instead an exhortation to professional historians to adapt their work to the “felt necessities” of the present, Von Rankean notions of perfect objectivity be damned. It’s a call for better and more relevant scholarly production—even if, as Becker himself acknowledges, Everyman rarely reads “our” books, the books of professional historians like him or yours truly.

Everyman’s own memories, in Becker’s opinion, “fashion for him a more spacious world than that of the immediately practical,” with most of the scraps of factual knowledge that he acquires derived from his mostly unconscious work as a popular culture bricoleur: “information, picked up in the most casual way… from knowledge gained in business or profession, from newspapers glanced at, from books (yes, even history books) read or heard of, from remembered scraps of newsreels or educational films or ex cathedra utterances of presidents and kings, from fifteen-minute discourses on the history of civilization broadcast by the courtesy (it may be) of Pepsodent, the Bulova Watch Company, or the Shepherd Stores in Boston.”

Becker’s proposed solution, then, is that we professional historians must work to ensure that Mr. Everyman’s weltanschauung is shaped by more than just the detritus left in the sieve after his daily skimming and browsing is complete. Thus, through our useful and frequent contributions to the public-intellectual sphere, a somewhat more enlightened Mr. Everyman might one day become acquainted with the meanings of borrowed words and phrases such as bricoleur, ex cathedra, and weltanschauung.

I appreciate Becker’s address and dislike it. I believe he’s right—history must be “made useful” for Mr. Everyman, in some generic sense—and therefore lectured to ingenuous freshmen in a manner that reflected this belief. But it pains me to concede that he’s right, and it pains me to make history useful because, in the course of doing so, I’m indisputably engaged in doing “history from above.” In fact, a more fitting title for “Everyman His Own Historian” might be “History From Above Directed Below, Delivered With Partially Concealed But Nevertheless Patronizing Superiority” (try saying that 10 times fast!). Having studied under Marcus Rediker, I recognize the value of doing “history from below” as a means of achieving various social justice objectives. But even this “history from below” still originates “from above,” prepared for public consumption by trained scholars. It’s not naïve history that approximates the “outsider art” of, say, William Blake or Henry Darger.

Much naïve or “outsider” history that would fit such a definition seems at first blush unworthy of professional scrutiny. Shambolic, sprawling family genealogies—my father produced one such effort that grew to 300 incomprehensible single-spaced pages—often amount to little more than DIY chronicles of dates and events interspersed with equal parts fiction and speculation. Historical societies dedicated to the categorizing of ancient baseball box scores or the pedigree records of legendary cats and dogs represent antiquarianism at its silliest. If this is the kind of history that Mr. Everyman busies himself producing, what utility could it have for us seasoned professionals?

Let me turn to professional wrestling for an answer. In 1999, the hardcore wrestler Mick Foley inaugurated an unusual sub-genre of DIY history when he published his autobiography, Have a Nice Day: A Tale of Blood and Sweatsocks. The central conceit of the book was that Foley, one of the few wrestlers who’dearned a college degree, had written it himself. It became an improbable bestseller on the strength of Foley’s surprisingly insightful prose and thus solidified his own standing among the sport’s all-time greats. More importantly, though, it convinced many has-been professional wrestlers—a group of individuals accustomed to monetizing every aspect of their lives—that they could earn a few bucks from preparing their memoirs with the aid of a ghostwriter.

The years following the publication of Have a Nice Day have witnessed an unprecedented efflorescence of “as told to” wrestling narratives. Athlete autobiographies have long been a catalog staple at many publishing houses, but these Foley-inspired manuscripts were neither instructional manuals by top stars nor bowdlerized just-so stories of living legends. Many were initially published by Essays on Canadian Writing (ECW) Press, which found a niche as a purveyor of such works, though the vast majority are now independently published, like the multiple excellent works authored by my friend—and fellow Splice Today contributor—Ian Douglass.

As alarming as it is to admit, Goodreads reports that I have read more than 150 of these books since I started using that site in 2009. My interest in this sport, widely and perhaps rightly regarded as a trashy and prurient spectacle by some of its highbrow critics, betrays my own rural and low-culture origins, but that’s an insufficient explanation for why I spent four hours of adult life reading the autobiography of Dewey “The Missing Link” Robertson. Or five hours reading Bill Watts’ The Cowboy and the Cross.

It was “source work,” I kept assuring myself. It’d serve as the basis for a future project of some sort. How, exactly? As the basis for a monograph that addressed the history of professional wrestling in a thematic manner, with chapters on race, class, masculinity, etc.? Oh sure, that’d be the “hook” for solicitation letters sent to scholarly presses, on account of how no extant single-author work treats the subject in that way. But there was something else I wanted to know: what were all of these authors doing in their memoirs? Why were they cataloging all this naïve history?

A book such as Tony Atlas’ Too Much…Too Soon does address the issue of racism in the sport, and Jody “The Assassin” Hamilton’s The Man Behind the Mask contains racist content, but neither offers a fraction of the insight on that subject that can be found in a few paragraphs of George Schuyler’s uproarious Harlem Renaissance satire Black No More; then again, one wouldn’t expect them to. Rather, what emerges following a long immersion in this material is a profound fascination with the competing claims made by the wrestlers who produced it.

Each wrestler attempts to “put himself over” (i.e., to come off looking good) at the expense of his fellows—much as he did during his working career. To Jody Hamilton, Tony Atlas was a lazy and undisciplined worker. To Atlas, Hamilton was an old-school Southern racist. Dozens of autobiographies address the notoriously brutal and ingenious Mid-South wrestling promoter “Cowboy” Bill Watts, an ex-Oklahoma football player regarded as a hero to some, a jerk by most, and “double tough” by everyone (most notably Watts himself, who uses his autobiography to confess to innumerable crimes, including ripping out someone’s eyeball and eating a human ear, in the course of his stock Christian redemption narrative).

If I were to organize this material into a manuscript suitable for publication, I’d do it a disservice. To make it “useful,” I’d have to impose on it an order “from above.” Tony Atlas and Jody Hamilton will be quoted for specific purposes, their words removed from the context of the narratives that Scott Teal compiled for them. The amateur historians who took it upon themselves to write chronicles of various wrestling promotions will suffer a similar fate. They merely wanted to preserve the record of a specific match or storyline; now excerpts from their work will have to stand in for something ostensibly greater and more significant.

Everyman doesn’t, as Becker tells us, make his history out of whole cloth, but rather out of the factual fragments that surround and rush past him. What he fastens firmly in the front of his mind and what we professional historians would like him to remember are two very different things. Tony Atlas would have you remember him as a wrestling star, and I would have you treat him as a couple of disembodied sentences in my monograph. This is, admittedly, an insoluble problem for those of us engaged in ransacking the grab-bag of history. Yet ransack we must, because we can.

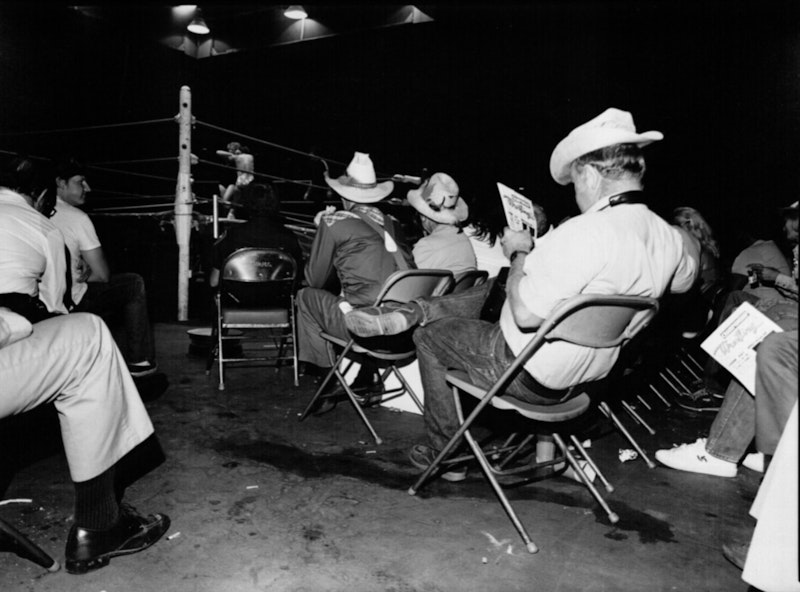

—Image credit: University of Texas at Arlington Library, Ringside Exhibition