Pop music is unoriginal—an undifferentiated sea of liquid plastic goop. One song sounds like the next, and they all sound like prefab nothing; written by no one for everyone in a perfect circle of featureless anonymity.

That’s the general criticism, anyway. And the new Faith Evans album, Something About Faith, doesn’t give you a whole lot of room to argue. Mid-tempo ballads blur into slightly faster than mid-tempo dance-floor thumpers blur into somnolent guest raps by the likes of Snoop during which so little is happening that you can actually hear the silent electronic shifting of digits as his fee gets deposited in his bank account. Even the track names have a tranquilizing, inevitable drone. “I Still,” “Way You Move”, “Party,” “Right Here,” “Your Lover”, “The Love in Me”—it’s like she took phrases randomly from a databank of every R&B song title of the last 20 years.

In contrast to this bland gush, I’ve been obsessed over the last few weeks with classic torch songs. Unlike Evans, torch singers like Sarah Vaughan, Julie London, June Christy, or Ella Fitzgerald all cultivate a unique sound, including a repertoire of original songs, wildly different instrumentation, and….

Well, actually, no. Classic torch songs are in a lot of ways more formalized than contemporary R&B. The jazz backing is quite predictable—and, indeed, when it’s unpredictable, and you get lots of big band shenanigans, I tend to get irritated and wish they’d shut up and just let me hear the singer. My favorite albums are ones like Vaughan’s stripped down After Hours or Christy’s Duet with just her and Stan Kenton’s piano.

If the instrumentation in torch songs is little varied, the songs themselves are even less so. Where Evans picked song titles that sound like every other song title in the genre, torch singers are more direct; they just sing the same songs. “Summertime,” “Every Time We Say Goodbye,” “Black Coffee”—you buy an album of torch songs, you get the same playlist, or close to it. If you didn’t—if someone was filling their album with Beatles covers, for example—you wouldn’t say, “Oh how sparklingly original!” You’d be peeved.

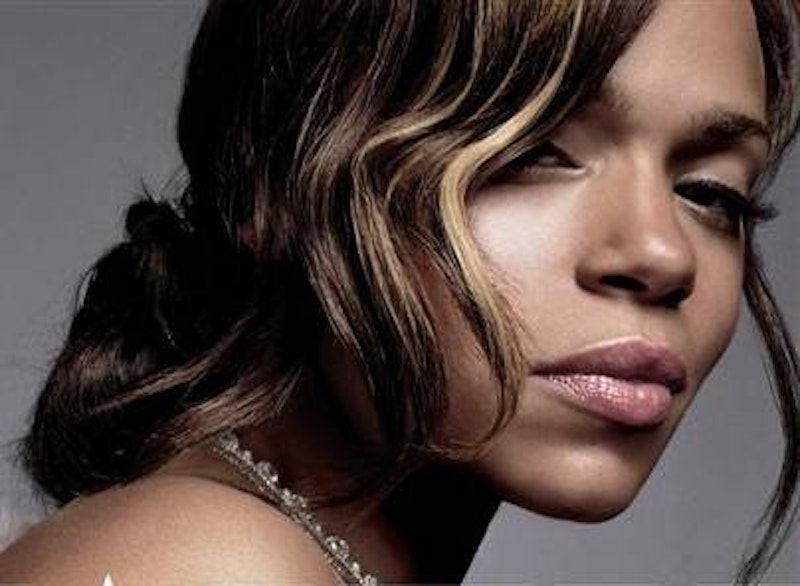

Of course, you could argue that the difference, the originality, is in the singing. No one on earth sounds like Sarah Vaughan, with her multi-octave leaps and relentless swing, or like Julie London with her sensual almost whisper. But the truth is that Faith Evans’ rich, burred voice is quite distinctive in its own right. When multi-tracked, it’s warm and sun-drenched with just an edge of yearning—hard to resist even when, as on this album, it’s being employed in the service of pap.

And maybe the pap is the point. To some extent it is the singer not the song…but at the same time, the song can make the singer. I’m not a huge Ella Fitzgerald fan; her perfect articulation and general chipperness seems staid compared to many of her peers. But when she launches into “You’re the Top”, bouncing over lines like “You're the top! You're Mahatma Gandhi. / You're the top! / You're Napoleon Brandy. / You're the purple light / Of a summer night in Spain, / You're the National Gallery / You're Garbo’s salary, You're cellophane.”—well, she doesn’t sound bland. On the contrary, she sounds sophisticated and playful. She didn’t write those words, but by saying them she becomes as witty as Cole Porter—maybe even wittier, given the insouciance with which she rhymes “Gandhi” and “Brandy”.

The songs on Something About Faith, on the other hand, are all original—Evans even had a hand in producing a couple of them. But they don’t give you any particular sense of her personality except, you know, that she’s in love and has been hurt in love and then she wants to go out and shake it at the club

There is one exception. “Gone Already” features washes of production by Carvin & Ian and lyrics that actually show a spark. “I was feeling like a dead man walking / numb from all the pain you're causing / hoping that things would change.” It’s not Cole Porter, but coupled with a memorable melody and Evans’ resigned vocals, there’s suddenly a personality there. The song isn’t necessarily less clichéd than any of the others, but it at least takes the trouble to sell the cliché.

Which is perhaps the case with art in general. There’s not much that hasn’t been done or said before. “Originality,” then, doesn’t actually mean a new invention. Instead, it’s a convenient way to sum up a list of more amorphous virtues—craft, genius, or whatever it is that makes the same old song sound new.

Something About Originality

Faith Evans' new album is a cliched pop mess, but maybe that's okay.