Justin Mitchell’s album, The Garden Of Earthly Delights, is lovely: funny, quirky, jazzy, funky, surreal and avant-garde all at the same time. It’s like the soundtrack to a drive-in science-fiction zombie movie set in a haunted fairground on the outskirts of town. It’s a meditation on mortality and what it means to be alive in this cockamamie world. The first track, “Rapture for Rupert,” is a multi-layered fanfare rising to an echoing crescendo. It sets the mood for the rest of the album.

The Rupert in question is Rupert Hayes, the maverick artist from my hometown of Whitstable who died on July 9, 2018. He and Mitchell were good friends. Hayes’ old studio went up in flames recently, so it’s fitting that Mitchell’s tribute should be heard not long after that event. Although obviously informed by Hayes’ passing, there’s a joyous, life-affirming quality to the album, as if Mitchell is finding ways to stay optimistic despite the ever-present shadow of death.

“Pigeons,” the third track, is a celebration of the mysterious ordinariness of the world. Musically it’s like a sound painting of what pigeons do when they’re gathered, cooing on a rooftop. There’s a nodding quality to the rhythm, like a sonic representation of a pigeon’s movements. After a while the words of a poem are heard, read by Emily Firmin, Mitchell’s long-term partner in art at Total Pap, the papier-mâché studio they run together. The words and the music combined create an evocation of the sight and sound of a band of pigeons scattering about, pecking for food.

Lines like “nodding raptors lost in rapture” and “bobbing lovebirds lost in games, clapping wings with self-applause” are precisely fitting for the theme. At one point Firmin laughs aloud, obviously delighted at the words she’s being asked to read.

“A Cautionary Tale,” the fourth track, is an allegory of the absurdity of our current world: “A dazzling fairground, lights all on, with spinning rides and tempting prizes…” with a mouse atop a unicorn getting his comeuppance. Mitchell creates characters that come alive. Both the mouse in “A Cautionary Tale” and the pigeons in the previous track have that quality. They come alive in the listening, as does the anonymous narrator in “Requiem,” with his dark observations about life told to a stranger he accosts in a bar, full of chilling ill-humor and grim pessimism: “Love is dead, they say… A banquet laced with lies, that is eaten on the hoof.”

The tune sounds like something that Bernard Herrmann might’ve composed for a Hitchcock movie, and has all the looming threat of that misanthropic director’s classic period: Strangers on a Train meets Shadow of a Doubt round the back of the Bates Motel.

“Hangman’s Holiday” is like a dance tune with death as its theme. The video features a dancing skeleton or two. Nevertheless, the music is jaunty and the tone is upbeat.

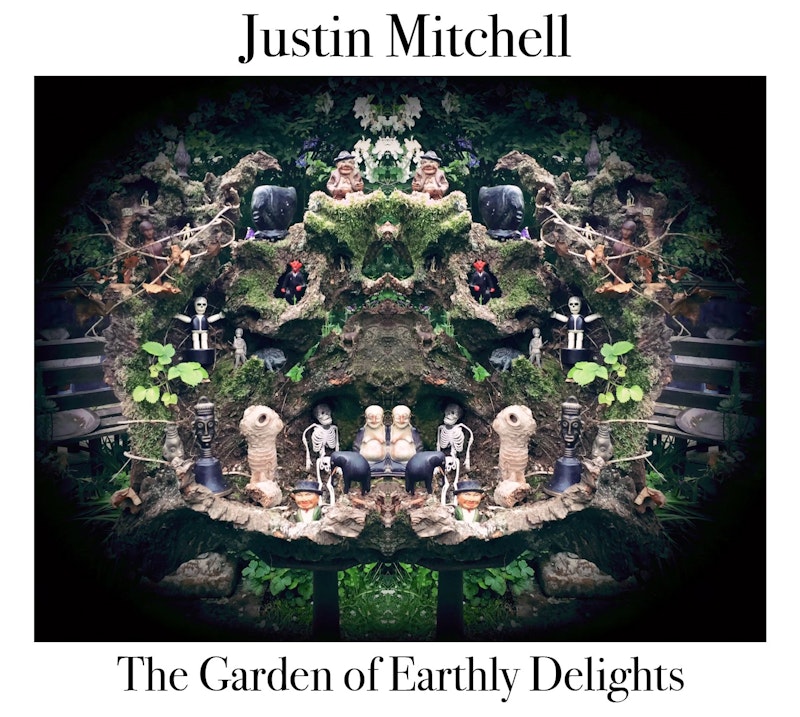

I won’t go through all the tracks. Many are instrumentals with a cool jazz or funky feel. The title track is a reference to the 15th-century surrealist masterpiece by Meister Hieronymus Bosch, currently held in the Museo del Prado in Madrid. It’s a good title and tells you, in an oblique way, what the album’s about. The triptych painting shows you the Garden of Eden on one side and Hell on the other, with Life on Earth squeezed in between.

I asked Mitchell what his musical process was: how he came to write this album. He said: “I start by playing around with ideas on the keyboard without consciously thinking about it too much and recording at the same time on a little eight-track digital recorder. I’ll develop an idea and start extending it. I might then start adding other ingredients. I’ll try not to overwork it or worry about the framework but concentrate on putting down a solid foundation. It could go in any direction, but it has to have plenty of things that I didn’t mean to do in it: that way I can listen to it in a more divorced way. Then I might leave that and start another idea, do the same, come back to previous ideas—always slowly building on it.

“I had no idea where each number would go on this album, but was aware that they were all part of each other and that the common theme would make itself known in time. It’s my first solo musical project and, although it was very liberating, working by myself I have become aware of the limitations of doing things like this on your own—apart from the fact that there is quite simply a hell of a lot of things to consider in terms of artwork, technicalities of production and the practical side of things.

“The creative side I’ve tried to let happen by itself as much as possible, without worrying about what box to push it into. I wanted it to sound broad and representative of the richness of life with its joy and its pain but, again, working on your own in a tiny room has it limitations, as I said. Instrumentation-wise, I would’ve really liked to have real drums and real bass, but in the end things are what they are—and we’re just very lucky if we have something we look forward to getting stuck into when we wake up.”

The fact that Mitchell managed to get such an accomplished sound out of working on his own in a tiny seven-foot room stuffed with instruments makes you wonder what he might’ve achieved in a full-size studio with a real band at his disposal. Musically, I hear echoes of Hugh Masekela and Robert Wyatt. I suspect this is probably because they are both, like Mitchell, trumpet players. Wyatt probably has similar working methods, confined to a studio in his home, and putting the music together mainly on his own.

The parallels with Wyatt remind us that, as a member of Soft Machine, he was one of co-founders of that historically important musical form known as the Canterbury Scene. Mitchell was also involved as the trumpet and keyboard player with the Happy Accidents, an imaginative jazz-leaning bunch led by Canterbury musical guru Graham Flight, a veteran of the Wilde Flowers, a band that numbered Kevin Ayers, Richard Sinclair, Hugh Hopper and Robert Wyatt in its ranks as the 1960s turned psychedelic.

—You can buy the album (and listen to the tracks) here: https://justinmitchell1.bandcamp.com/follow_me.