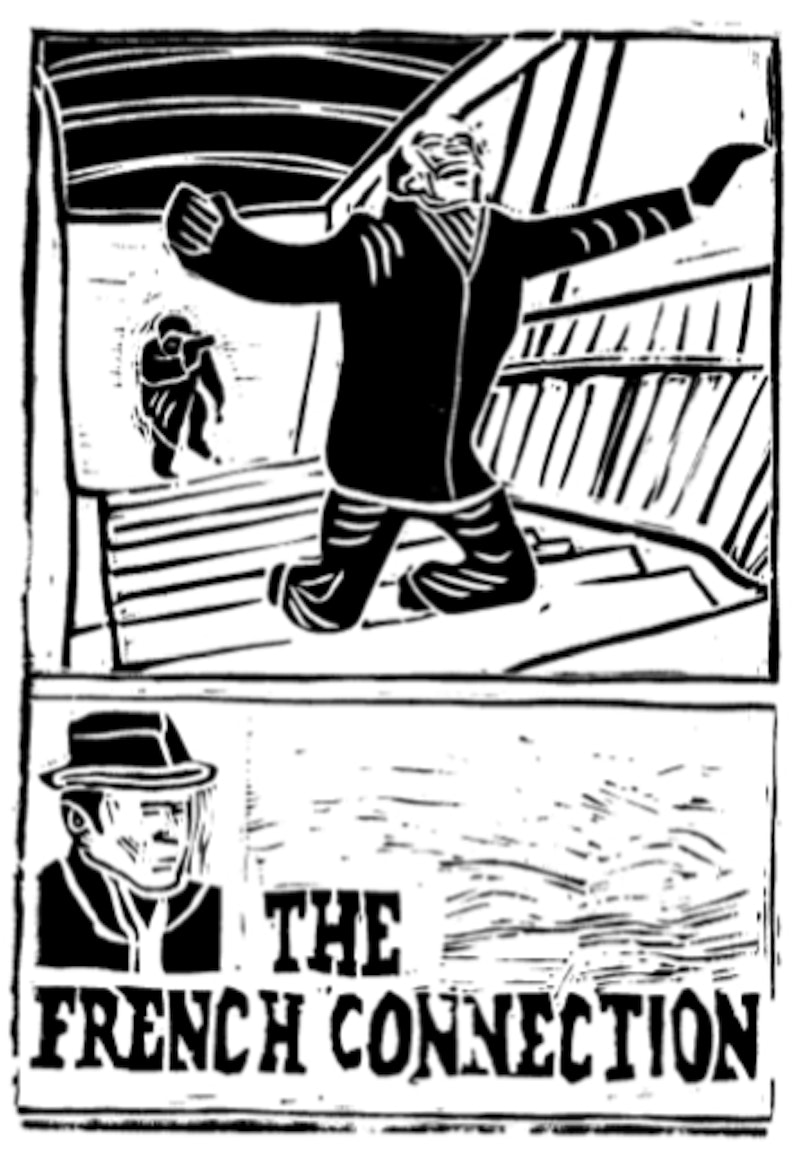

The French Connection is a 1971 police thriller starring Gene Hackman and Roy Scheider. Hackman plays Jimmy “Popeye” Doyle, a racist, trash-talking cop chasing drug smuggler between France and New York. Based on the life of actual NYC Detective Eddie Egan, who broke a drug smuggling ring in 1961, the film features the most famous car chase in movie history.

William Friedkin was a young, unknown director with four movies under his belt. He’d just made the unpopular gay-themed film The Boys In The Band and his career was going nowhere. He called legendary filmmaker Howard Hawks for advice. Hawks told him, “People don’t want stories about people’s problems or any of that psychological shit. They want action stories.”

The French Connection was Friedkin’s stab at an action film. This was the Vietnam era and the movie reflected the murky morality of the period. The hero is gruff, unsympathetic and not afraid to shoot bad guys in the back. The villain is suave and likable and, in true anti-genre fashion, he gets away with his crime in the end.

The lead role of Doyle was turned down by a spate of Hollywood stars. Steve McQueen felt the movie was too much like Bullitt. Lee Marvin hated New York City cops. James Caan feared the character was too unlikable. Jackie Gleason called the story depraved. Robert Mitchum thought the screenplay was garbage. Peter Boyle turned down the role because he wanted more romantic parts. Amazingly, the role was initially given to New York newspaper columnist Jimmy Breslin, a non-actor. Breslin was fired after Friedkin learned he didn’t know how to drive.

Gene Hackman had burst on the scene in 1967 after his appearance in Bonnie And Clyde. Friedkin gave the role of Doyle to Hackman without the benefit of an audition, script reading or screen test. When reading the screenplay, Hackman cringed at the racist dialogue he had to utter. Only after spending a week on the New York streets with Eddie Egan, did Hackman realize the dialogue reflected real life.

The film starts out slow for an action movie. An hour goes by without any gunshots. The story focuses on the drudgery of police work, the uneventful stakeouts, the hours of paper work. Cops slowly cruise city streets looking for criminals. Details are subtle, the tone brooding (much like Scorsese’s Taxi Driver that came out five years later). The film has a documentary feel, as if we’re watching unedited B-roll from early 70s New York. At one early point we can see the first World Trade Center tower under construction in the background.

When the action finally kicks in, it’s relentless. The highlight is a scene where a car chases an elevated subway line through the streets of Lower Manhattan. The chase was not in the original script. Producer Phil D’Antoni, who also produced Bullitt (with its memorable San Francisco car chase), suggested the idea to Friedkin. Details were improvised on a last-minute location scout.

The chase was filmed without obtaining proper city permits. Traffic was cleared for five blocks in each direction and the filmmakers shot between 10 a.m.-3 p.m. Off-duty NYPD officers teamed with assistant directors to direct traffic. The producers had permission to control traffic signals on streets where they ran the chase car. But the chase illegally spilled onto streets where there was no traffic control, forcing stunt drivers to evade real cars and pedestrians. The crash that occurs midway through the chase involved a local man who was driving to work when his car was suddenly struck by the picture car. He wasn't hurt but producers had to pay for his repairs.

A camera was mounted on a car’s bumper for low-angle POV shots of the streets racing by. The camera was under-cranked to 18 frames per second enhancing the sense of speed. Famed stunt driver Bill Hickman drove at 90 mph for 26 blocks without stopping. Friedkin wanted a hand-held camera in the back seat. His camera operators, all of whom were married with children, felt the scene too dangerous. Friedkin, young and single, operated the camera himself.

Hackman did some of his own stunt driving until he struck another vehicle and crashed into a concrete pillar. At this point, the producers pulled the plug. Friedkin lacked the coverage he wanted, but he made do with the footage. The final scene has no music, only the ambient sounds of screeching tires, car horns and smashing metal. Friedkin said he edited the scene to the tempo of Santana’s “Black Magic Woman.”

The French Connection spawned an era of documentary-style cop movies dedicated to gritty authenticity and morally ambivalent characters. The film won five Academy Awards. It was also the first R-rated movie to win Best Picture.

—See more Loren Kantor at: http://woodcuttingfool.blogspot.com/