This is part of a series on fascism in film. The previous entry, on Salon Kitty, is here.

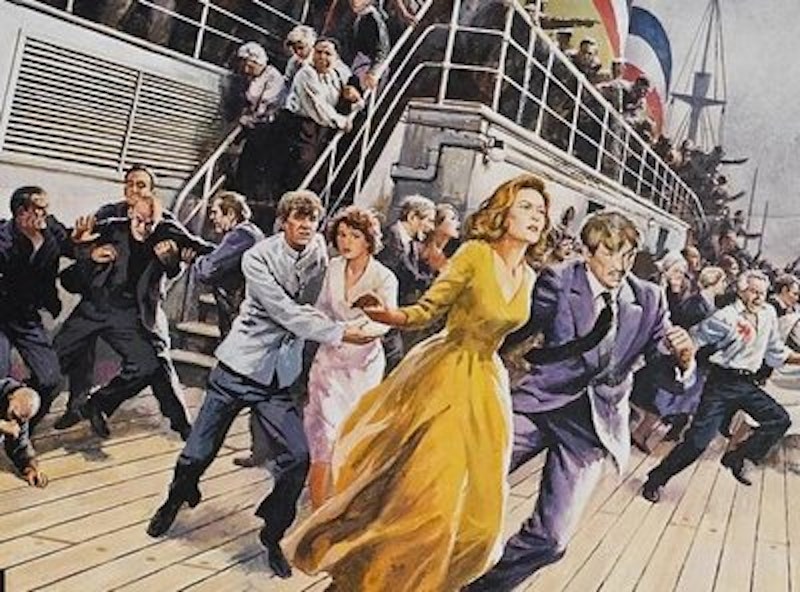

Voyage of the Damned (1976) is one of those bloated, prestige Hollywood Oscar-bait dramas that never won an Oscar. At nearly three hours, the based-on-a-true-story tale of the German ship St. Louis and its cargo of Jewish refugees fleeing Nazi persecution was, perhaps, trying too hard even for the Academy. Slowly, the ill-fated vessel makes its way across the Atlantic to be turned away from both Cuba and the United States as A-list actors are trotted out to chew scenery and shovel ham. Orson Welles as a Cuban businessman spews great gouts of world-weariness while his much younger female companion hovers in the background to underline the decadence; Max Von Sydow as noble, tortured Captain Schroeder projects tortured nobility; Faye Dunaway as passenger Denise Kreisler looks stunning wearing fabulous clothes and has unmotivated dramatic tension with Oskar Werner playing her husband. Numerous less famous actors go mad in Shakespearean, pitched-to-the-cheap-seats fashion.

There’s a prostitute with a heart of gold; a doomed shipboard Jew/Gentile romance; a noble plain-spoken Jewish-American fighting for what's right; and a villainous Nazi bully who shouts "hate me, I'm a Nazi!" every time he comes on screen.

The bloviating, bluster, and melodrama are overwhelming—but even so, they can't quite conceal that the movie isn't very Hollywood at all. In fact, the dramatic business seems so excessive in part because it's unnecessary. If Hollywood and the public never took to Voyage of the Damned, it's not because they were put off by the excessive sententiousness or ginned-up staginess. It's because the film, almost despite itself, grasps a cold truth—the Holocaust was not inspirational, and it didn't have a happy ending.

The really successful Hollywood Holocaust narratives feature iconic gentile saviors. Schindler's List (1993) and the recent The Zookeeper's Wife both focus on non-Jews who bravely resisted the Nazis by launching clever, successful plots to smuggle Jews away from the SS and certain death. In these films, good will, courage, and a little luck can defeat the forces of evil—the evil conveniently personified in Nazi officials, whose iniquity is clearly demonstrated before their inevitable humiliation. Virtue triumphs, injustice is defeated, and the filmgoers are encouraged to fight evil too.

Voyage of the Damned has sympathetic good-intentioned gentiles too. The captain of the St. Louis is not a Nazi party member; he treats the Jews onboard with dignity and respect, and is prepared to wreck his ship off the shore of Britain to get his passengers asylum. Various officials in Cuba are sympathetic to the Jewish cause, and work on their behalf. The captain's steward Max (Malcolm McDowell) falls in love with one of the Jewish passengers. One of the other crewmembers refuses to act as a spy for thuggish party enforcer Otto Schiendick (Helmut Griem), and spits in his face.

The difference between Voyage of the Damned and more lauded gentile savior narratives is that all of these acts of gentile resistance and sympathy don't actually save many. The Cuban official obtains visas for two children, but that's all he can do; the other 950 odd passengers are beyond his help. Max the steward can't save his Jewish girlfriend or himself; the two of them end up committing suicide together rather than sailing back to Europe, where the camps wait. The German who spit in the Nazi's face is immediately beaten to a pulp by Nazi goons, and thrown off the ship to his death.

Even the captain's good will is ineffectual. As it turns out, he doesn't have to crash the ship into a reef; at the last minute, Britain, Belgium, France, and Holland all agree to take a portion of the refugees on the ship. This is the happy ending of the film; the narrative concludes with the refugees celebrating the good news.

But text on screen after the action ends informs the viewer that this news wasn't so good after all. Shortly after the refugees were resettled, World War II began. People resettled in Britain were safe, but Germany conquered most of continental Europe. Many of those on the ship were eventually captured by the Nazis and sent to concentration camps. The film estimates that 600 of the 950 passengers were killed in the death camps.

If the ship had landed in Cuba, no one would’ve died. The Nazis were counting on Cuba, America and (though this isn't shown in the film) Canada refusing the refugees. The Nazis let the ship go, then broadcast propaganda about how undesirable and awful the Jewish escapees were. People always hate foreigners anyway, and the public in Cuba and the United States had little interest in receiving a boatload of stigmatized rejects then, much as the U.S. under Trump has decided that they don't want to receive Syrian refugees.

The Cuban authorities and FDR both came to the same political decision; the ragged refuse was too much trouble. The Cuban president explains his primary responsibility is to the Cuban people; "My conscience is clear." Roosevelt doesn't even have to explain anything; he's never shown. And so, the Nazis reap a propaganda coup; they've shown the world that no one wants the Jews. Who can complain, then, when the Third Reich solves the Jewish problem in its own way?

In many Holocaust narratives, there's a stark choice between doing the right thing and saving innocents on the one hand and doing the wrong thing and letting people die on the other. Voyage of the Damned provides a less clear-cut, and therefore much bleaker, picture. People make moral decisions casually. The public vaguely mutters, "We don't want refugees"; politicians throw up their hands and say, "We have to listen to the public." The wheels of prejudice and cruelty grind on.

And against this blind force, the resistance of people of good will is largely ineffectual and inconsequential. People have divided loyalties—the Nazis threaten the captain's family back home if he intervenes on behalf of his passengers too enthusiastically. For that matter, the captain was chosen specifically because he was not a party member, and so would seem more trustworthy, giving a patina of legitimacy to the propagandistic voyage. Good intentions can pave the way to the gas chamber.

People often use the phrase "the banality of evil," but Hollywood rarely shows fascism as banal. Even the title of The Voyage of the Damned suggests gothic horror and skeletons hanging in the rigging. The film struggles to avoid banality, ladling on blood, romance, sex and drama.

But the narrative, accidentally or otherwise, shows fascism and its collaborators operating with day-to-day, tedious pettiness. A hold-up at the border because you don't have the right paperwork; the knowledge that those guys can beat you up and the police will do nothing; distant people in power weighing public opinion about whether you should die. You don't really need a lot of evil when you can kill people with officious indifference. The damned are damned not because they're journeying to some terrifying hell, but because they're not really journeying anywhere. Go halfway across the world and you find what you left—the same Nazis blandly nursing the same unspectacular hate.