This is the final essay in a series on fascism in film. The previous entry on Defiance is here.

In this series on fascism in film, I've written about different kinds of movies. The Eternal Jew is outright propaganda by the Nazi regime. Salon Kitty is sexy S&M Nazisploitation. The Believer is about neo-Nazis in the US. Dirty Harry is a quasi-fascist law & order fever dream. Night and Fog and Voyage of the Damned are historical meditations on or dramatizations of events of the Holocaust.

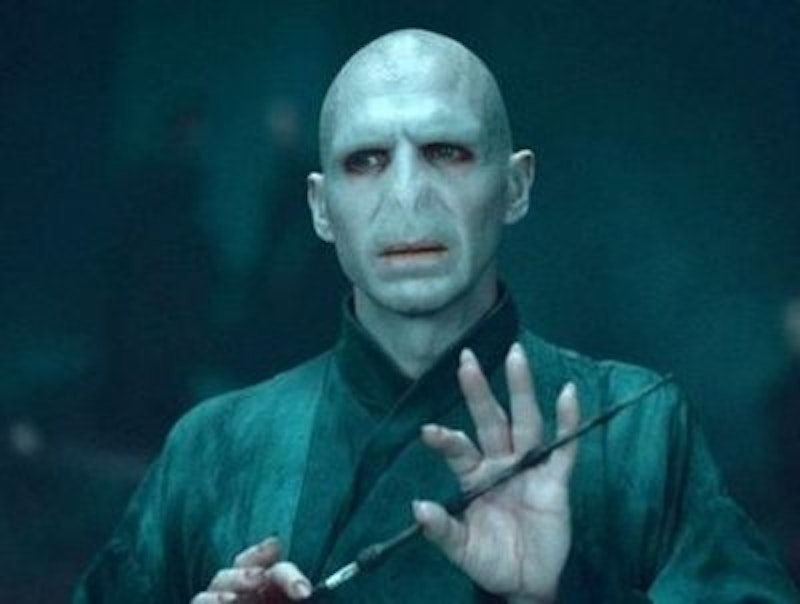

The series hasn't really touched on what is probably the most common and most banal representation of fascism in film, though: the fascist super villain.

Hitler-like world conquerors are ubiquitous on screen—though their very proliferation often makes the connection to Hitler seem almost irrelevant. From Voldemort and his hatred of muggles to Sauron and his totalitarian eye; from the eugenically perfect Khan in Star Trek to the eugenicist Hugo Drax in Moonraker planning to kill all non-perfect humans; from the Nazi-referencing Storm Troopers in Star Wars to the Nazi-referencing WWI German soldiers in Wonder Woman—the Nazis in film are a shorthand for evil. WWII stands as a kind of quintessence of villainy, an apogee of malevolence. The Good War echoes on in Hollywood, as hero after hero battles some half-sketched simulacra of a Hitler simulacra on screen after screen, forever.

Hitler and the fascists did terrible things and Nazi ideology really is evil. It's not a bad thing for the movies to reiterate that prejudice and totalitarianism are bad, even if they do so in pursuit of a fairly simple-minded adrenaline rush. As Tom Hitchner noted at Splice Today, anti-Trump protestors frequently carry signs saying things like, "Mudbloods Against Bannon." J.K. Rowling's Voldemort is a fourth-generation pastiche of super-villain Hitler pastiches. But he can still be a convenient stand-in for evil when people are honestly trying to do good. "Don't be Voldemort" may not be the most profound way to phrase that ethical statement, but slogans aren't meant to be profound anyway. They're meant to rally people, and "Don't be Voldemort" is at least reasonably likely to rally people to the right side. Hollywood regularly promulgates lousy cultural messages and stereotypes: "The police are the good guys;" "heroes deserve a thin blonde woman as a prize;" "people of color are malevolent and/or disposable." Given the choice between those ideas and "fascism is bad," I'll happily choose "fascism is bad" every time.

There are two problems with Hollywood's brand of bland anti-fascism, though. The first is that it's neither specific nor insightful. Hollywood's super villain Nazis rarely engage in targeted racism or discrimination against the groups the Nazis hated, or against groups who face marginalization in the present. Hollywood encourages its viewers to feel the cathartic thrill of combating Hitler without actually committing to opposing the parts of Hitler's ideology that are most salient in the world around us. Heroes get to fight the super villain Hitler out there, without necessarily having to deal with super villain Hitlers closer to home—which is how the U.S. retained our own fascist homegrown Jim Crow even after defeating Germany.

Super villain Hitlers often rant about world conquest, and/or threaten to kill lots of people, and/or mouth some sort of quasi-eugenic ideology. But those elements of fascism are scrambled and spliced together on film, which makes it difficult to see how the pieces fit, both historically and in situations where fascist threats might be currently politically relevant. As just one example, the manic, sweeping anti-leftism of fascist movements is hardly ever represented on screen. People don't know that the main internal German resistance to Hitler came from communists and socialists, and Hollywood isn’t eager to tell them.

The heroes who fight fascism in Hollywood are non-ideological, centrist American do-gooders, whose vision of freedom and justice involve a vaguely capitalist status quo—they're people like Humphrey Bogart in Casablanca, motivated by generic decency, rather than by any actual left commitments. With the memory of fascist anti-leftism erased, people have trouble seeing extreme, belligerent anti-leftism from places like Fox as a fascist warning sign—and hacks like Jonah Goldberg can even babble about "liberal fascism," cheerily spitting on the graves of all the socialists Hitler murdered.

As Goldberg shows, anti-fascism divorced from its historical grounding or ideological commitments can end up being used for purposes other than anti-fascism. It can even be used to validate fascism itself. Nazi ideology was an exercise in projection; Hitler justified his genocidal race war by arguing that it was really the Jews who were engaged in a genocidal race war against the Germans. Voldemort is Hitler—but the undead aristocratic, plotting Voldemort also harks back to vampires and Nosferatu, with its rat-like anti-Semitic caricatures. Khan in Star Trek is Hitler—but he's also associated with a power-mad Oriental east, and therefore again recalls Hitler's attacks on Jews. 300 is both a brief against a fascistic imperialist Persian empire and an openly fascist film, which pits free virtuous white Westerners against debased effete people of color.

Americans almost universally hate Hitler. Yet we elected a racist authoritarian. There should be a contradiction there. But watch Hollywood films, and it's clear that there doesn't have to be. It shouldn't be shocking that Hollywood's anti-fascism is vacillating and ineffectual. Hollywood isn't interested in fighting Nazis; filmmakers just want easy tropes on which to hang their action-film plots. Even in WWII, American anti-fascism was more circumstantial necessity than thoroughgoing heartfelt commitment; we no sooner declared war on the Axis than we set up our own camps for the marginalized. Will the United States fight Sauron, or give him a toupee and put him in the White House? You'd think it would be a stark choice, but watching Hollywood movies, you wonder if Americans can tell the difference.