Gay teens are four times as likely to commit suicide than their non-gay peers. The reason is pretty simple: many gay teens are mercilessly tormented in high school, and can look for support to neither their parents nor school administrators. Isolated, they often see no end to the abuse or to their unhappiness. As sex advice columnist Dan Savage said, “When a gay teenager commits suicide, it's because he can't picture a life for himself that's filled with joy and family and pleasure and is worth sticking around for.”

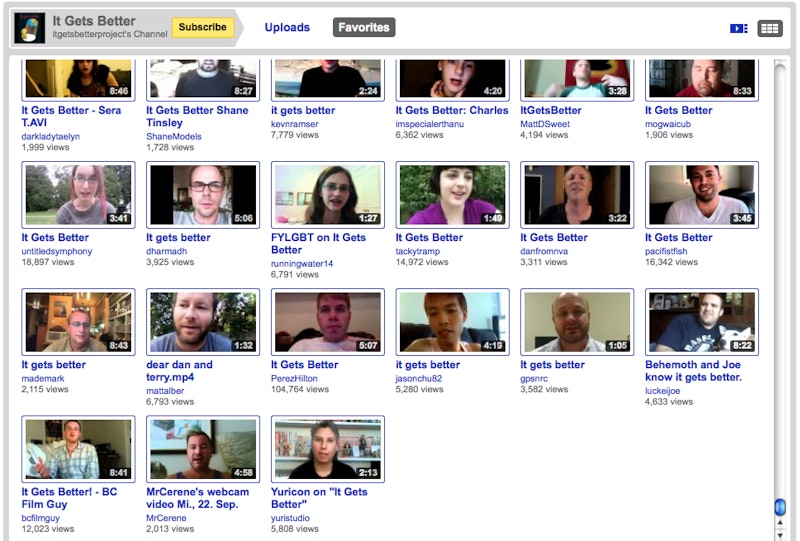

To try to address this situation, Savage has organized a YouTube channel where adult gay men and women can record messages directly for gay teens, telling them that their lives will improve the moment they get out of high school. As Savage’s husband Terry says in their joint video, “Honestly, things got better the day I left high school. I didn’t see the bullies every day, I didn’t see people who harassed me every day, and I didn’t need to see the school administrators who would do nothing about it every day. Life instantly got better.”

I’m a straight guy who had a reasonably pleasant adolescence. Still, I did go to high school, and I have some sense of how terrible it can be. As such, I’m certain that Savage is right, and that more information, and more hope for the future, will help gay kids—and perhaps even prevent some suicides.

Nonetheless, I find the message in the videos I’ve seen frustrating. Yes, it’s good for kids to know that things will improve. But high school isn’t a force of nature. It’s not a hurricane, or even acne. It’s not unavoidable. If high school is making your life miserable beyond all endurance—so miserable that you’re seriously considering killing yourself—then maybe you shouldn’t wait two or three years for your life to get better. Maybe you should just drop out.

People often consider dropping out of high school as if it’s an unmentionable, unpardonable sin—something solely for losers and failures. And it is true, obviously, that dropping out of school can have negative effects on your career prospects, earning potential, and life in general. However, if the choice is between “worse career prospects” and “suicide,” I think most people would agree that they would take the worse career prospects. Dropping out may not be ideal, but it’s not the end of the world. Suicide, on the other hand, is.

In any case, the choice between “finish high school” and “work a service job for the rest of your miserable existence” is a false one. I have a very good friend who dropped out of high school, never got her high school degree, and then graduated from the University of Chicago, got two masters degrees, and now works doing environmental resource management on Chicago waterways. As Grace Llewellyn wrote in The Teenage Liberation Handbook, as far as getting into college or getting a job, “Neither depends on graduating from high school.” Instead of going to school, Llewellyn argues, kids can learn more by pursuing what interests them, whether it’s horseback riding, history, sports, or even video games.

Obviously, Llewellyn is a big old hippie. She promotes “unschooling,” home schooling without a curriculum, where kids figure out what they want to do and then do it, just as if they were, you know, human beings. I’ve got some problems with hippies too, but Llewellyn convinced me. Her book is a little breathless, but it also provides a breadth of resources, examples, and strategies for making unschooling work.

I realize, though, that skipping through the daisies and being free, free like the tree spirits isn’t for everyone. Many kids would find Llewellyn ridiculously impractical, to say nothing of their parents. But you don’t have to unschool in order to get out of high school. On the contrary, especially with the Internet, there are numerous options for teens who desire a high school diploma but don’t want to be tormented literally to death to get it. I worked for 14 years at (and still do occasional freelance projects for) a correspondence high school called the American School, which offers a very affordable degree program through the mail. There are lots of other programs as well, some of them through colleges like Brigham Young University and Indiana University. These schools are accredited and they offer, not a GED, but a high school diploma of the exact same type that would get through a regular brick-and-mortar school.

There are other possibilities too—for instance, a student who dropped out of high school could take some classes at a community college, or possibly even go right on to freshman year at school in some circumstances. The point is there are options other than just waiting around in misery in the hope that someday things will improve.

It’s true that all of these options require effort and some hurdles. If a student’s parents are opposed, any change is going to be difficult. But knowing the possibilities can be a big step on the way to getting approval. Most parents probably don’t even know that correspondence school exists, for example.

It’s also worth noting that, in this instance, gay students actually benefit from the fact that high school is horrible for everyone. Not that gay youths don’t, in most situations, have it worse, but the general misery of high school can work admirably as camouflage. You don’t need to come out to your families in order to explain why you want to leave school; on the contrary, you can point to the resources available as a sign that leaving school is normal. Grace Llewellyn’s book isn’t aimed at gay kids in particular. Gay students need these options more than others, but they’re not especially gay-targeted, which means that using them doesn’t need to be part of some painful coming out revelation.

There are arguments you can advance as to why kids should stay in school. All of them, though, evaporate in the face of the very real threat of vicious, prolonged abuse and potential suicide. And while it’s valuable to tell kids that things will improve someday, it’s also worth remembering that “someday” is a really, really long time for a teenager. Teens are people, not potential people; they deserve to have bearable lives now, not in two to four years. Kids need to know not just that they may be better off someday, but that they can get out now. And there’s no way they can know that unless we tell them.