“You Don’t Have to ‘Imagine’ That John Lennon Beat Women and Children—It’s Just a Fact," a story by Lauren Oyler for the Vice satellite site Broadly, has been passed around on social media since its publication on September 10. It’s filed under the category “You Know Who Sucked,” alongside other inflammatory pieces about people like Albert Einstein, Gandhi, Mother Teresa, Dr. Seuss, Lou Reed, Florence Nightingale, Grover Cleveland, and Salvador Dalí. They beat their wives, hated women, and treated their loved ones like shit.

This is all abhorrent behavior that needs to be acknowledged in order to temper our perception of historical figures that got away with horrible things while being anointed as saints and geniuses beyond reproach. Chris Brown, Bill Cosby, and James Deen haven’t been so lucky, and they were rightly pilloried by a generation obsessed with defaming and punishing celebrities. But not every victim of “callout culture” raped their girlfriend or beat their children. Policing language in pursuit of a more enlightened and progressive culture might be a good idea, but the way it’s carried out every day on Twitter reminds me of The Scarlet Letter, a new outlet for people to sate the shaming impulse in us all.

Justine Sacco’s tweets about getting AIDS in South Africa might’ve been stupid and unfunny, but did she deserve to have her life ruined? We make sport out of turning people into pariahs because we can’t just round them up in the town square and ring the shame bell anymore.

Another post by Oyler: “Hey Rude: John Lennon Mocked Disabled People on Stage,” with the subhead: “A newly discovered video reveals more of what we already knew about the wife-beating Beatle: He sucked.” Well, the attached footage of Lennon shouting and clapping like a spaz has been widely available for 20 years since it was featured in The Beatles Anthology. Oyler offers no context for Lennon’s behavior, content to condemn him and leave it at that. The Beatles were exploited by guardians and caretakers for the mentally disabled, who used their incapacitated patients as entree to meeting The Beatles themselves. How could they refuse an audience with the handicapped and mentally ill without being condemned by the same manipulative monsters that put them in that position? Lennon’s imitation and black humor may have been rude, but it didn’t spring forth unprompted from his cold, black heart. Bob Dylan’s line about “Lies that life is black and white” goes both ways: not every Muslim is a terrorist, and not everyone that crosses a line on stage or online is an irredeemable bigot.

Lennon’s sainthood remained untouched for many years after his death. When Albert Goldman published the venomous The Lives of John Lennon in 1988, he was public enemy number one, denounced on television and in print, mocked on Saturday Night Live, and widely regarded as a muck-racking scumbag who took glee in smearing Lennon’s legacy with all the sordid and lurid details he could find on the late Beatle. These are not new discoveries, and cheap hit pieces like Oyler’s serve no one but oblivious Millennials who can’t separate the art from the artist. I thought The Beatles were an evergreen, but in the past five years it’s become extremely passé to be a Beatles fan. Yet The Rolling Stones are inexplicably hip again, despite their own formidable history of abuse. Who’s ringing the shame bell for Mick or Keith?

I feel like a broken record bringing up Lindsey Buckingham again, but until he gets his own entry in “You Know Who Sucked,” I’m compelled to note his especially fucked-up relationship with Carol Ann Harris, whose memoir Storms came and went without much attention at all. It’s a damning document of Buckingham’s emotional neglect, hair trigger temper, and psychotic episodes of violence, the worst of which involved Buckingham grabbing Harris by her hair, dragging her across their gravel driveway, getting in his Mercedes with one hand on the wheel and another still gripping his girlfriend’s head by her hair, and driving up and down while Harris begged him to stop. Fleetwood Mac is also very hip again (maybe for the first time ever?), and the same people who trash and dismiss Lennon have worn out their parents’ copies of Rumours and cite Buckingham’s brainchild Tusk as a masterpiece to collect cool points.

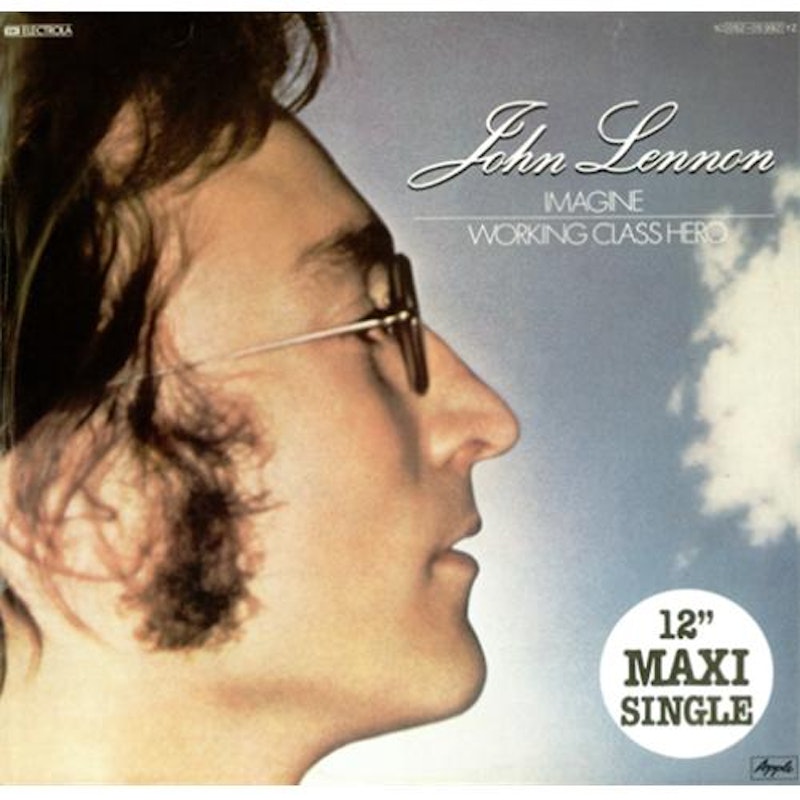

Lennon’s “Imagine” has been criticized since it came out in 1971, mostly for the line “Imagine no possessions/I wonder if you can.” I didn’t experience the rise and fall of The Beatles in real time, so I’m not surprised fans like my dad and uncles scoffed at the song as maudlin, cloying, and insufferably hypocritical, coming only a year after the blistering John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band. But “Imagine” has transcended its flawed author and endured as a universal “secular hymn”: it remains the go-to song for dealing with violent tragedies like 9/11, last month’s Paris Attacks, and Lennon’s own murder in 1980. Katy Waldman wrote an excellent piece for Slate in the wake of Paris attacks, asking “Why Do We Always Turn to John Lennon’s ‘Imagine’ After a Violent Tragedy?” She writes that “Though Lennon imagines nothing less radical than the toppling of all religious, economic, and social institutions, his vision is wistful and unfulfilled; he’s dreaming, not doing. […] This is the least coercive call-to-action in the history of revolutions. ‘Imagine’ belongs to the tradition of hymns or spirituals that visualize a glorious afterlife without prophesizing any immediate end to suffering on earth.” Despite the current wave of anti-Lennon sentiment, “Imagine” continues to resonate around the world because its message and beauty remain even when stripped of its lyric. This video of a pianist playing an instrumental version of “Imagine” outside the Bataclan went viral immediately, just one day after the Paris attacks.

Lennon’s tacit doubt in himself and humanity’s ability to “live as one” is what makes the song so moving to me. Waldman writes, “That tentativeness is part of what makes the song so appealing in the days after a tragedy. No one who has just watched footage of families mourning their loved ones in the wake of a terrorist attack is ready to swallow a dose of unalloyed affirmation. The song seems veined with the sad understanding that its own dream is too simple—a fact echoed in a piano accompaniment as gentle as a rocking chair, a melody as modest as a lullaby.”

Other ubiquitous hymns and anthems like “Amazing Grace,” “God Bless America,” and “The Star-Spangled Banner” are pocked by the romance of war and submission to God—salvation for some, not all. Lennon’s song isn’t exactly humanistic: it betrays a deep-seated misanthropy and disappointment with the way things are, and a sense of defeat before destructive forces that are so insurmountable that all we can do is dream as a distraction. The song’s profound melancholy and resignation comes from the realization that its dream is destined to fail, that we will never live in the world that it invites us to imagine. But in the face of unfathomable violence and infinite sadness, to dream and wish the impossible is all we can do. In 1981, Ringo Starr reminded Barbara Walters that ”[Lennon] said 'imagine', that's all. Just imagine it.”

—Follow Nicky Smith on Twitter: @MUGGER1992