I've always been taken by records wrapped in weird or interesting backstories. So often context can illuminate the work and make listening to the music more mysterious and enjoyable. Listening to My Bloody Valentine's Loveless, you can hear the years-long struggle and the ultimate success of the sound; the obscurity and eccentricity of Van Dyke Parks' Song Cycle makes it feel like a golden Easter egg; on The Beatles’ White Album, you hear the sound of a band breaking apart. The stories of how these songs emerged and the events that shaped them strengthen the meaning of the work, and bring us closer to the mindset of the creator at the time.

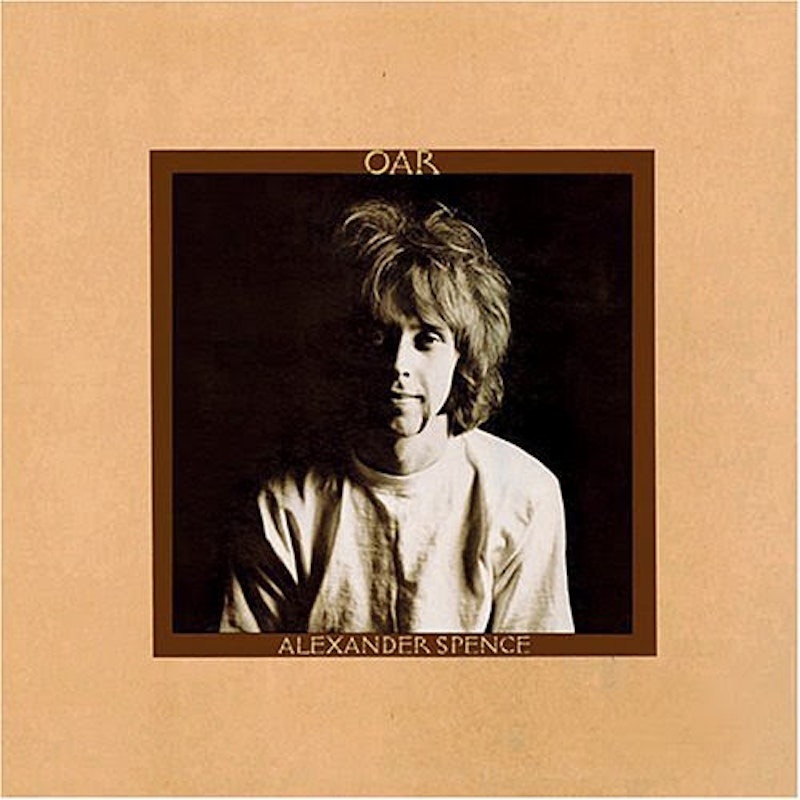

Skip Spence, best known as a member of 60s psych groups Moby Grape and Jefferson Airplane, recorded his only solo album Oar in 1968 after an involuntary stay at a psychiatric ward in New York. Spence had tried to slaughter his Moby Grape bandmates with an axe while tripping on acid, and in came the men in white coats. Oar is the product of that hospital stay, a woozy and lackadaisical folk record full of cracks, fractures, and rough edges. The songs lilt along at a narcotic pace and move through irregular chord sequences and abrupt time changes. Spence sounds as doped up as the band, and his lyrics shift from lovelorn laments to cutesy sing-song ditties to oblique psychedelic garble, never betraying a comfortable walking rhythm. Parts fall in and out of time, as mistakes and studio banter appear periodically. Even though the album's sessions were months after Spence's hospital stay, these songs are undeniably the work of an unstable individual, or at least someone with a fragile head.

It's good not to read too much into the personal lives of artists to compare to their work—after all, Bob Dylan beat up his wife, but that doesn't make "Sad Eyed Lady of the Lowlands" any less beautiful. Knowing that Oar is the work of a mentally ill man makes it all the more sad and damaged sounding, and because of the no-frills, fly-on-the-wall character of the recording, it feels like a snapshot of where this guy's head was at after too much paranoia and too many psychedelics. Of course the record sold nothing when it was released (it was quickly deleted from Columbia's catalogue and forgotten); even without the loony bin backdrop, this is still an unsettling group of bizarre folk songs. But strangely, it doesn't feel delusional or insular at all—Oar is comfortable, and doesn't have anything to prove. It's just there, in all its friendly strangeness.

The Comfort Of Oar

Skip Spence's first and only solo album.