"You should have been around for the beginning of Twitter," a young writer named Stephanie told me about a year ago, "It was great then. It's terrible now."

It took me about 10 months and 800 tweets of my own to figure out what she meant. Twitter is a social networking site like any other, a living organism of interaction, born by humans and possessing a life cycle all its own. I decided to play phenologist and study the rise and future fall of Twitter, tracing its journey from "great" to "terrible."

Birth

Twitter is much more personal than a typical website. Readers choose their own content from a list of authors based on the author's identity: from famous to everyday, friends and strangers alike. By subscribing, the reader gives a vote of confidence to the author, that they will read the author's posts with some measure of faithfulness, that they will follow their triumphs and trials alike, mushroom trips and trips to the DMV. What you're saying when you subscribe to a Twitter user is simple, yet touching: "I care about you."

At its beginning, I believe that this is what Twitter was like. A relatively tiny network of people who cared for each other, sharing anecdotes and aphorisms in 140 characters or less. They replied and re-tweeted, rejoicing in the glow of their computer screens. It was a bit like the 1960s, as I picture it. A brand new online community. The dawning of the age of Twitter.

Growth

As with all great tragedies, it was to be Twitter's great strength—its passivity—that would lead to its demise. The Internet itself is a mostly-passive entity. The user delivers a small input (the web address) and is given a relatively enormous amount of information in return. Small inputs can yield huge responses. An afternoon can be wasted on article after article for the price of a few clicks. The effort it takes to produce this bounty of information immeasurably eclipses the amount of effort it takes to view it. The abbreviation “TL;DR” (“Too Long; Didn't Read”) exists because even the reading itself is too much work sometimes.

But what about those of us casual web browsers who want to create content, too? We want to leave our mark on the Internet, but lack the time, motivation or money to create and update our own site. Enter Myspace and Facebook. These sites are website-building machines where we go to construct sites devoted to our favorite topic—ourselves. Browsers no longer had to learn acute languages like HTML or CSS to participate in the Internet. And they could search for friends with similar interests or histories. No wonder they were wildly popular. But they still didn't make the Internet easy enough. Both Facebook and Myspace had the infrastructure built for users to start their own blogs, but neither dealt with the fundamental problem of blogging: the writing part. Writing is hard. Most of the articles on the Internet today are made up of hundreds of words.

Twitter's innovation was to do away with many of the basic requirements of blogging. No more HTML formatting, no more image tags. Hell, no more images. Twitter's character limit provided an excuse for lazy grammar ("your" takes up less space than "you're," not to mention "yr"). Updating had never been easier. People would go months before updating their websites, weeks without changing their Facebook profiles, but could update Twitter a dozen times a day.

Twitter instantly transmits the smallest user input to all of their followers, creating easy, passive access to a field of readers almost guaranteed to care about the author. The network had grown 1500 percent in just three years, up to four billion Tweets per quarter in early 2010. The environment was ripe for infection.

Infection, Decline

Most would infer that the death of Twitter was at the hands of the megacorps that signed up for accounts after their marketing departments realized the opportunity for free publicity. Hundreds of "exciting" yet inoffensive posts later and Twitter effectively bled itself dry of any decency. The truth is that by the time Nestle and Dow Chemical started Tweeting, there wasn't much decency left to destroy.

Pinpointing the beginning of the end of any social network is a bit like isolating Patient Zero in an outbreak. It's a lot easier to describe the conditions that would foster an infection rather than it is to locate the first case.

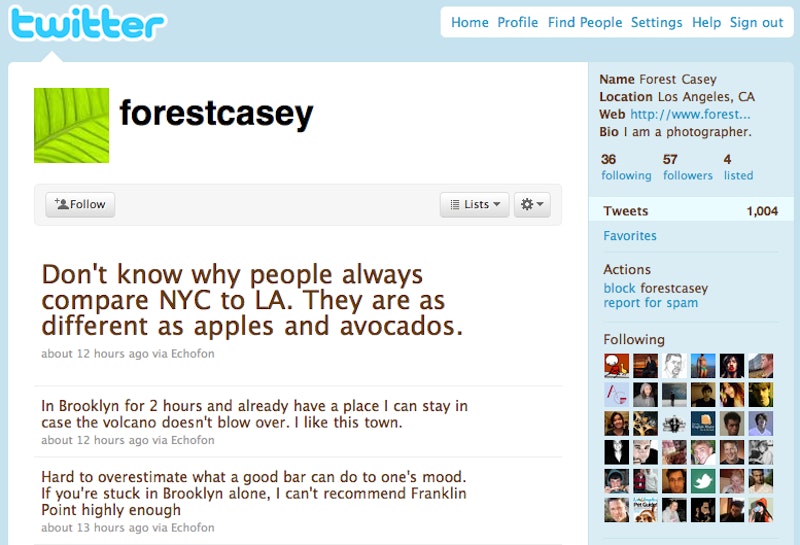

It would all have been very innocent. Patient Zero logged on to Twitter to tell the world about an upcoming stand-up showcase or poetry reading. Maybe it even happened on Twitter's opening day in 2006. After this first promotional tweet, the infection spread. Actors, artists, and businessmen quickly realized that the more Twitter subscribers they collected, the more exposure their work would receive. Thus began a mad dash for followers. Soon, you couldn't log on to the site without hearing about some new blog in search of some hits or a charity in need of a donation. In Los Angeles, I see Tweets for improv classes, improv practice and improv shows. My Twitter page has turned into an indecipherable field of bit.ly links to sites I don't want to visit. Original content is disappearing. One Hundred Forty characters is turning into TL;DR.

And the worst part of this is that it's inescapable. Twitter has made self-promotion so simple, so passive, it's impossible to resist. I've started Tweeting about my new articles, sending one more ad adrift in a sea of solicitations.

Death*

Prognosticating the obsolescence of today's technology has become something of a sport among tech writers. A product or service is barely allowed the time to crawl, let alone walk, before it's declared too old to move.

And yet, the death of a website is more complicated than that. For every magazine piece about the death of Myspace, there are a hundred bands creating profiles and posting new tracks to their profiles, giving the site a reason to exist. There are still, in 2010, active accounts on LiveJournal and Friendster. My thesis notwithstanding, Twitter is not dead and will not completely die anytime soon. If anything, the site still has room to grow in popularity. But for every additional friend comes another passive promoter. Stephanie, my young writer friend, thought this was enough to spoil Twitter. She's since moved to Spain. Her Tweets, once a steady stream of fresh content, have slowed to a trickle of re-Tweets. How long before she starts avoiding Twitter altogether?

That special, idealized community that established Twitter has grown old since 2006. Their voices, the original writing that made Twitter such a special place, have been washed out by the tide of regurgitated content and self-promotion. The new population cares more about Justin Bebier than Health Care Reform; the former was a trending topic in March of 2010, the latter wasn't. If Twitter is, as Evan Williams said, an "information network" rather than a "social network," what does it say about the site when the information presented is more timely than meaningful, when its trending topics are more trendy than relevant?

Old websites rarely die; their traffic just gets directed to the next site—Friendster begat Myspace, which begat Facebook and Twitter. The never-ending forward progress is reason enough to register your name at Chatroulette, or the next new networking site, just in case the next thing becomes the next big thing.